I know Alastair from his visits to my shop, which are always extremely enjoyable. As well as being a competent and sensitive violinist and violist, he is a true academic - both infinitely interested and extremely knowledgeable about a broad range of musical and non musical subjects. Here is his monograph on Nicolo Paganini, which is entertaining and filled with nuggets that I didn’t know. Well worth taking the time to read!

Nicolo Paganini (1782 – 1840)

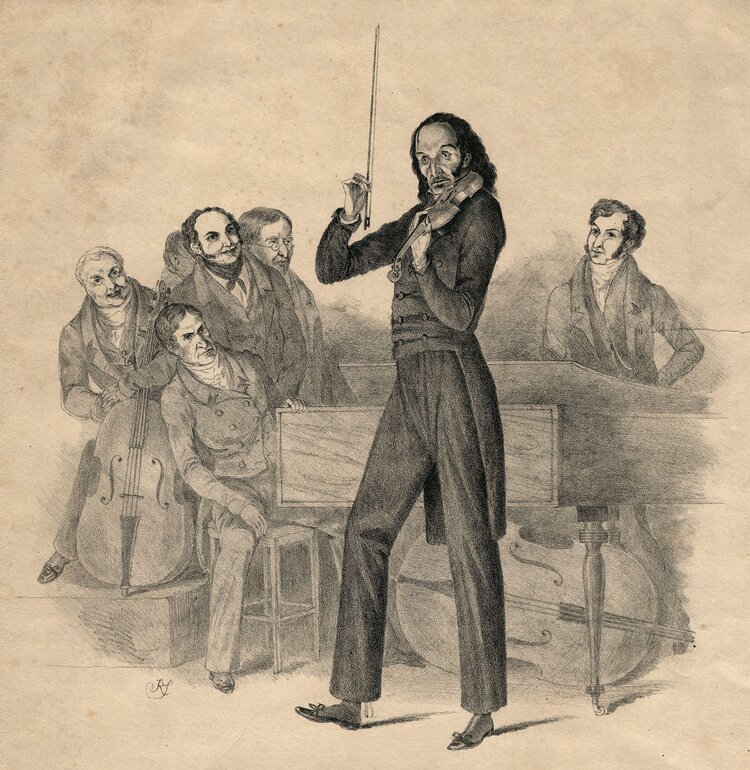

There have been many virtuoso player-composers, particularly among violinists. A quick glance at reference books will yield plenty of names, all celebrated in their time, some of whose works are remembered and performed still, a few well-known – Corelli, Tartini, Locatelli, Arditti, Nardini, Biber, Viotti, Bazzini, Rolla, Vieuxtemps, de Beriot, Spohr, Rode, Joachim, Wieniawski, Gade, Godard, Svendsen, Ernst, Ole Bull, Sarasate, Kreisler. In the 19th century and still today two names stand out – Franz Liszt among the pianists and Nicolo Paganini. As a young man, Liszt held audiences in awe, and he had the stage manner and tricks to maximise this. In particular, women were affected by this hugely handsome young man with the flowing locks and the commanding manner who played like a god, his eyes fixed sightlessly on some invisible distant beauty, swaying and crouching at the keyboard with the music, even occasionally affecting to faint and recover as the power the music and his playing of it overcame him. Many young women fainted in reality at his concerts – you really do need to think of Beatlemania without the shrieking (and with better music). One noble young lady carried round her neck at all times a gold locket which contained, of all things, a cigar stub the great virtuoso had discarded. Liszt was, however, a considerable composer, not just a mesmeric matinee idol. So it was also with Paganini the performer, whose spell held an extraordinary sway over the European musical public during his years on stage – and of course he composed too, with some distinction, though he was no Liszt in that respect. He undoubtedly deserved the acclaim he regularly received – his most virtuosic compositions give evidence to his extraordinary gifts as a player – but in addition part of his allure undoubtedly lay in his audience’s inability to believe what they were hearing. This slight, rakish, frail-looking man could not possibly be producing the sounds they heard. He must be possessed; the devil must be at work in him. It was not natural, not possible, beyond human. Even more than Liszt, all too sexily human if divinely gifted, Paganini the player held a thrall that no other performer has ever held, or perhaps ever will hold.

He was born in Genoa on 27th October 1782, the third of six children, His father was a trader and semi-professional mandolin player, and that was the instrument that young Nicolo took up at the age of five. By seven he was playing the violin and showing extraordinary promise, so that by his teens he was giving concerts. Under his father’s care and with the help of capable teachers he progressed at an extraordinary rate, but he outgrew all that and at the age of 18 went to Lucca to pursue an independent life and career. By that time, he displayed the three outstanding characteristics which would remain with him all his life – he was an unbelievable virtuoso, an obsessive gambler and an inveterate womaniser.

In 1805 Lucca was annexed by Napoleonic France and Paganini came to know, and know very well, Napoleon’s sister Elisa, who became infatuated with him. He played for the court and gave lessons to her husband, Felice. When she became Grand Duchess of Tuscany, he moved to Florence with her and her court but in 1809 left to pursue an independent career. Hugely famous locally, and now well-connected, he was as yet unknown in wider Europe and the days of his international fame lay ahead and would do so for many years.

As a composer Paganini’s works can be categorised into three groups: display pieces which often have little real musical value, some of them employing particular tricks or special effects – bar after bar of consecutive octaves, hair-raising artificial harmonics, cascades of notes at extreme tempi and so on - meltingly beautiful slow pieces with little or no virtuoso element (he had the Italian gift for a beautiful melodic line, just as Verdi and Puccini would do later on) and works which combine the two, virtuosic display which is not just display for its own sake but musically worthwhile too. This last category is well exemplified in his Opus 1, the 24 Caprices. They are virtuoso studies, 2 minutes to 7 minutes long, which cover pretty well all of the technical challenges a violinist can face but also, very remarkably, are fine short pieces in their own right. If he had written nothing else, these would have marked Paganini out as a gifted, imaginative and sensitive musician, not just an incredible note-spinner. A good example is the fourth Caprice, in C Minor which at 7 minutes happens to be the longest. Paganini is testing the player’s skill with extended passages of legato chords, octaves and double stopping ; towards the end he introduces a more rapid, spiky coda before a very effective, affirmative climax; in so doing, he also creates something which works musically and is an effective piece.

Caprice No. 4 in C Minor

The Caprice which follows that, in A Minor, is clearly virtuosic and extremely difficult (and much shorter) but it’s still well-constructed and enjoyable. It is in fact possible to listen to all 24 Caprices right through and enjoy their ingenuity, variety and musicality. Even so, they are so testing that I know of only one violinist who played them publicly entire, and that well on in his career and with careful thought beforehand – the Italian Ruggiero Ricci, who made something of a speciality of virtuoso display (and was very good at it). To play all 24 must have been an incredible test of stamina. I wonder if Paganini himself ever did it? It‘s very unlikely - there is fact no record of him ever playing any of the Caprices in public.

Caprice No. 5 in A Major

By contrast, here are the variations on ‘God Save the King’. This is very much a 'see-what-I-can-do’ piece, good fun but rather outlandish. But Paganini could do what ordinary mortals could not do, and some of his music is intended to make just that point. The poor little tune is manhandled and pummelled into submission until, after just over 4 minutes it lies on the canvas exhausted, like the player probably.

Variations on ‘God Save the King’

But the man who wrote that could also write this –

Sonata No. 12. Op. 3/1

No display there, no showing off (except of a beautiful tone and melodic line). The Variations are fun, but the sonata is proper music!

Paganini’s fame began to spread following a concert at La Scala, Milan in 1813. Prominent European musicians got to hear of him and rivalries built up with other famous virtuosi composers such as Beethoven’s contemporary in Vienna, Louis Spohr. Paganini was no longer a young prodigy – he was 31 by then – but international fame became inevitable once people got to know. In 1828 he undertook a 3-year concert tour across Europe, starting in Vienna and stopping in every major European city in Germany, Poland and Bohemia. In Vienna his immediate success replaced the first giraffe ever seen there as the latest public sensation. Every baker stopped making giraffe biscuits, which were selling like, well, hot biscuits, and made Paganini biscuits instead (they tasted much the same but looked different). His sets of variations were particularly popular, often beginning with the kind of lyrical beauty that we have just heard and then spiralling off into unbelievable realms of virtuosity. It’s worth remembering that no-one heard Paganini’s work unless they heard Paganini – no CDs then. So you didn’t know what was coming next – would he play with the violin upside down or standing on his head??? – and that added to the thrill. Here are the variations on I Palpiti, Op. 13 – a lyrical opening leading to various eventual pyrotechnics. It’s appropriate to hear Paganini played, as here, by Zino Francescatti, the only modern violinist who held a direct link to Paganini himself. Francescatti, who died in 1991, was taught by his father, who was a pupil of Paganini’s last pupil, Sivori

I Palpiti, Op. 13 (Francescatti/Balsam)

Very exciting! And so Paganini offered to audiences works that only he could play. Mind you times change. Let’s go back for a little while to those Caprices. Here’s the first one, in E Major, which explores spiccato string-crossing – and it's Sarah Chang

Caprice No 1 in E Major (Sarah Chang)

That’s from Sarah Chang’s first CD, which she made in 1992 when she was nine. It's not known whether Paganini could play that aged nine, but then, he hadn't written it by then.

Paganini was an extraordinary individual in more than one way. He gave many concerts, but many he also cancelled, to the great disappointment of his admirers and, no doubt, the consternation of the promoters. His health was erratic. He may have been affected by Marfan Syndrome. He certainly suffered from syphilis as early as 1822. The remedy then was the taking of mercury and opium, which brought their own problems. In 1834 he became ill with tuberculosis and recovered but his health was further weakened by the experience. Other reasons for sudden cancellation of sold-out events included the common cold and bouts of depression which could last for months.

Legends abounded about Paganini. The most common was that he had, Faust-like, sold his soul to the devil in return for superhuman skill as a player. In a superstitious age, this was not a surprising assumption. He had many, many affairs and in 1825 fathered a son, Achilles Cyrus Alexander, with a singer named Antonia Bianchi. Achilles accompanied Paganini on his European tours and was instrumental in dealing with his father’s burial, years after his death. In a fairly recent film, ‘The Red Violin’ a Paganini figure, internationally celebrated and feted, plays best when in flagrante delicto with a female conquest. This is a grotesquely comical notion – the woman would be deafened and no doubt there was a possibility that the scroll of the violin would get stuck in her ear - but it did have the advantage for the cuckolded husband that, returning and hearing Paganini in supreme form, he could hurry through and stop his wife from misbehaving, unless of course music meant more to him than anything, in which case I suppose he could just listen to the unexpected and rather unsettling concert.

When Paganini became famous furth of Italy, he met and was befriended by great men – Rossini became a close friend, as did Berlioz. Berlioz wrote ‘Harold in Italy’ for him (which famously Paganini never performed) and Paganini admired his music without reservation, calling him ‘the new Beethoven’. A rich man, Paganini gave Berlioz, ageing and unappreciated, many gifts of money. Schumann was another who admired Paganini, and indeed he wrote piano accompaniments for the Caprices. In the last year of his life Schubert heard Paganini, and declared that an Adagio by the great virtuoso was ‘like an angel singing’. In his ‘Carnaval’ Schumann characterised Paganini, as he did a number of friends and musicians. Here is the Paganini variation, entitled Valse Allemande. Why Schumann chose to write a German waltz for the great Italian showman, I don’t know – but the virtuosity is there once the piece really gets under way. Perhaps the gentle tune and the contrasting fireworks are intended to show the two sides of the virtuoso.

Schumann: Carnaval – Paganini

Paganini wrote six violin concerti. They exhibit the usual Paganini traits of virtuosic display tempered by an often very attractive lyrical facility. His handling of the orchestra tends to be perfunctory, a characteristic he shared with Chopin – an orchestra was necessary in a concerto, but the soloist always took centre stage. Here’s the final movement of his First Concerto, played by Zino Francescatti.

First Violin Concerto, Third Movement (Francescatti/Ormandy)

One of Paganini’s best-known non-virtuosic pieces is his beautiful Cantabile, written originally for violin and piano, then in a version for violin and guitar.

Cantabile

... and with that beautiful piece we have another example of Paganini essaying a sophisticated, musically excellent, lyrical work. I wonder how far he was trapped by his reputation? - so that the expectation that he would do the impossible had to be fulfilled at his public concerts. Fortunately for him, he could. As for the Cantabile and like pieces, perhaps they were for private use at home, where his few listeners would wish to be delighted with no need for shock and awe.

We think of Paganini as a great violin virtuoso virtually without parallel, but in fact he also played guitar to the highest possible standard (it is said he learned it allegedly to please a lady friend, which certainly sounds plausible). He wrote for the guitar too. Here are three of the little ‘Ghiribizzi’, which means ‘whims’, and which he wrote in 1820 for a young player, ‘a little girl in Naples’, the daughter of one Signor Botto. In addition, he wrote no fewer than 37 guitar sonatas, music for violin and guitar, quartets and trios. His complete guitar music is on YouTube. If you can find them, try Nos. 29, 20 and 38 of the 'Ghibrizzi'. You will easily recognise the famous tune on which the middle (actually number 20 in the series) is based.

Ghibrizzi nos. 29, 20 and 38

In his life, Paganini possessed many unique instruments, among them 2 Guarneris, 2 Amatis, a Gofriller, a Bergonzi and no fewer than 4 Stradivari violins, one viola and one cello. But the instrument with which he was most associated was a Guiseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ which he named ‘Il Cannone’, the cannon, in other words the weapon with which he would conquer the world. He was given it in his teens by a wealthy businessman in Livorno, and he willed it to the city of Genoa, his home city, where it now rests in a glass case on exhibition in the Palazzo Doria-Turis. What tales it could tell!

In his last years Paganini’s health was poor. He suffered from an affliction of the vocal chords and, after his tuberculosis, retired to Italy and to one of his many houses, the Villa Gaiona in Genoa. He planned to publish his compositions and to teach, both of which he did. Napoleon’s widow, the ex-Empress Maria Louisa, heaped presents on him and made him director of the Court Theatre. However, he made his way back to Paris two years later and opened a casino there, a ruinous venture which ate up much of his considerable wealth. Physical weakness made concert-giving impossible and he returned to Italy again.

Even the circumstances of Paganini’s death and its aftermath were bizarre and theatrical. He died in Nice, having travelled there for a rest cure, on 27th. May 1840. However, he had not received extreme unction, and the Archbishop of Nice refused to allow an ecclesiastical funeral. His faithful son Achilles appealed to the Archbishop of Genoa, but without avail. The coffin rested meanwhile in a cellar. A petition to the Pope produced no known result other than that staple of indecision, an enquiry. However, one day in 1844 – four years after Paganini’s death – the body was removed by civil authority and taken to Polevra near Genoa. There it was buried in a provisional grave. Nine years later it was disinterred and taken to Villa Gajona near Parma and Achilles was given permission for the obsequies at the church of Steccata. In 1876 it was exhumed again and reburied in the cemetery at Parma. When, in 1896, that cemetery was closed, the mortal remains of Paganini were again exhumed and reburied, this time for the last time, 56 years after his death.

Paganini wrote over 50 compositions, some of which have even yet not been published. Others who met and/or admired him supplemented these in their own work. Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini is well known. Brahms wrote a set of piano variations on the same theme. Here is that famous theme, which occurs at the opening of the final Caprice, which is a series of variations on the theme, a musical form that suited Paganini as both player and composer as well as any other.

Caprice No. 24

Paganini’s masterwork undoubtedly was the set of 24 Caprices, a remarkable combination of pedagogical purpose with imagination, invention and sheer musicality. Of his concertos, the second has the best-known single movement, the last, with its attractive opening theme, returning again and again in the Rondo form, with the usual gymnastics in between. The orchestral part, as always, is functional, perfunctory in places, but perfectly well suited for its purpose, which is to provide a framework for the performer, who can show off all his skills of beauty of tone, variations of colour, special violinistic effects and unbelievable dexterity. Here it is to end this little tribute to a great and unique man.

Violin Concerto No. 2 – Final Movement (Rondo)